< — A Quincy Quarry High iQ Sports Story

— A Quincy Quarry High iQ Sports Story

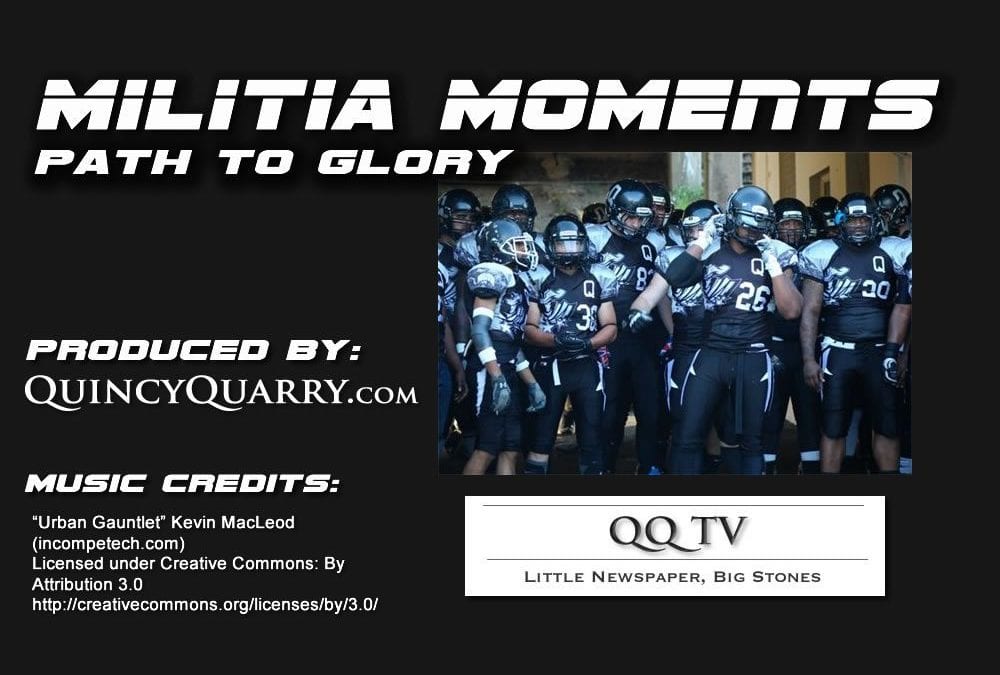

Coach Vaughn Driscoll’s Quincy Militia may only be 3-4 after Saturday night’s loss to the Worcester Mass Fury, but he believes his team is heading in the right direction and can begin making noise in the Eastern Football League soon.

Driscoll founded the Quincy Militia in 2009, but has been in football long enough to know a good team when he sees one. “It was years ago,” Driscoll recalled of his first experience with semi-pro football. “One of my former arch rivals Tom Deegan had started a semi-pro team called the Weymouth Sharks in 2005 and asked me to come in and coach.”

“I went in as an assistant coach, and in the second year he named me the team’s head coach. But after that season, the team started to fold so I came to Quincy,” he said. “They hadn’t had [a team] in eight years, and I thought maybe I could bring it back.”

Driscoll grew up and played football in Quincy so he was happy to bring semi-pro football back to his home town. But beyond his personal ties, he also believed he was making the right decision based on the town’s history with semi-pro football. When the Eastern Football League was created in 1961, it was the Quincy team that captured not only the first league title, but the second as well.

Driscoll grew up and played football in Quincy so he was happy to bring semi-pro football back to his home town. But beyond his personal ties, he also believed he was making the right decision based on the town’s history with semi-pro football. When the Eastern Football League was created in 1961, it was the Quincy team that captured not only the first league title, but the second as well.

But before he could create his own team, Driscoll had to find players. “I went to the Turkey Day game, Quincy vs. North Quincy, and passed out probably 500 fliers,” he said. The players and alumni players attending the game were very responsive to his idea, so Driscoll presented his new team to the league owners and the Quincy Militia were born in 2009.

Led by Driscoll, the Militia found success in their first season. “Our first year we went to the championship and got robbed on a horrible call,” Driscoll explained. Few expected the upstart Militia to compete in their first year, let alone reach the championship game. The Militia were taking on the Clinton Irish Blizzard, a team that was appearing in their third straight title game.

“This was a team that we had lost twice two during the season… we were 35 point underdogs to win the game,” he said. “We were down 14-0 in the game but we came back to tie it up. After that we picked off the ball and went downfield to kick a field goal.”

The kicker, Will Moore, was a former soccer player who had missed four game winning field goals to that point. But on the first football game his father ever watched him play, Moore drilled a 42-yard field goal through the uprights with three seconds to go in the game.

But he team’s excitement would be short lived. “All the refs said it was good, except the one on [the Clinton] sideline,” Driscoll said. “He threw the flag after we started celebrating.” Driscoll went out onto the field seeking an explanation, but the official responded by calling him for another penalty and moving the team 15-yards back. The Irish Blizzard blocked the second field goal and went on to win the game.

Driscoll suspects there was foul play at hand in that game. “I spoke to one of the players I knew from the Weymouth Sharks and he told me ‘We were celebrating that win before the game started.'” According to Driscoll the referee had familial ties to members of the Irish Blizzard organization.

He and his attorney wrote in protest to the league office, even going as far as to procure a copy of the game tape from a disgruntled Clinton player, and eventually the league admitted that the call should not have been made. But they would do nothing to amend the outcome.

“We asked to be named co-champions, since it was weeks after the game. We would have been the first co-champions in league history and we would’ve gotten our rings. But they wouldn’t have it,” he said.

“That set the tone for us,” Driscoll explained. “We had to battle so hard to keep our team together. If we had won, people would have flocked to come play for the Militia.” Not only did Quincy not become a desired destination among semi-pro players, but Driscoll struggled to keep his current players in town.

“Instead, I had to fight to keep the nucleus that I had. They stayed here for a couple years but after that they started to go in different directions. They thought the grass was greener elsewhere,” Driscoll said. “It’s been a fight every year to bring in new recruits and have them buy in that we can be that team that went to the Super Bowl.

The Militia began facing adversity after that loss. The team never achieved that level of success again, going 1-9 two years later in 2011 and 2-8 last season. But a revamped team has brought back Driscoll’s optimism.

He brought in a former player, Peter Kane, to take over his defense. “He’s done a stellar job,” Driscoll said of Kane’s work. “Our defense hasn’t been this good since year one.” He also brought in coaches Moe McNeil, and Joe Randolph to coach the offense.

Driscoll believes that Kane’s defense is among the best in the league. He said the key to success for the Militia is the offense. “If we get our offense clicking, we can go back to the title,” he said. “And anything can happen in the championship game.”

Driscoll thinks the addition of quarterback William Rondo, brother of former Celtics point guard Rajon Rondo, may have been the final piece of the puzzle. But while the goal will always be to win a title, Driscoll takes pride in what he has built.

Many of the players bring their family members and children to the games to watch and cheer for them. “We call ourselves a family before a football team. That’s something we want our players to bring home,” he said. In at least one case, the bond is more than camaraderie. Defensive End Aaron Smith now plays on the same team as his son, Maurice Vance, a linebacker.

“We really want to get Quincy more involved,” Driscoll added. “I don’t ever want to go back to not having semi-pro football in Quincy.” If the team really does begin to win again, he should have no problem keeping the Militia in Quincy for a long time.

]]>