<![CDATA[

– A tribute from the New York Times written by Alex Halberstadt and covered by Quincy Quarry News.

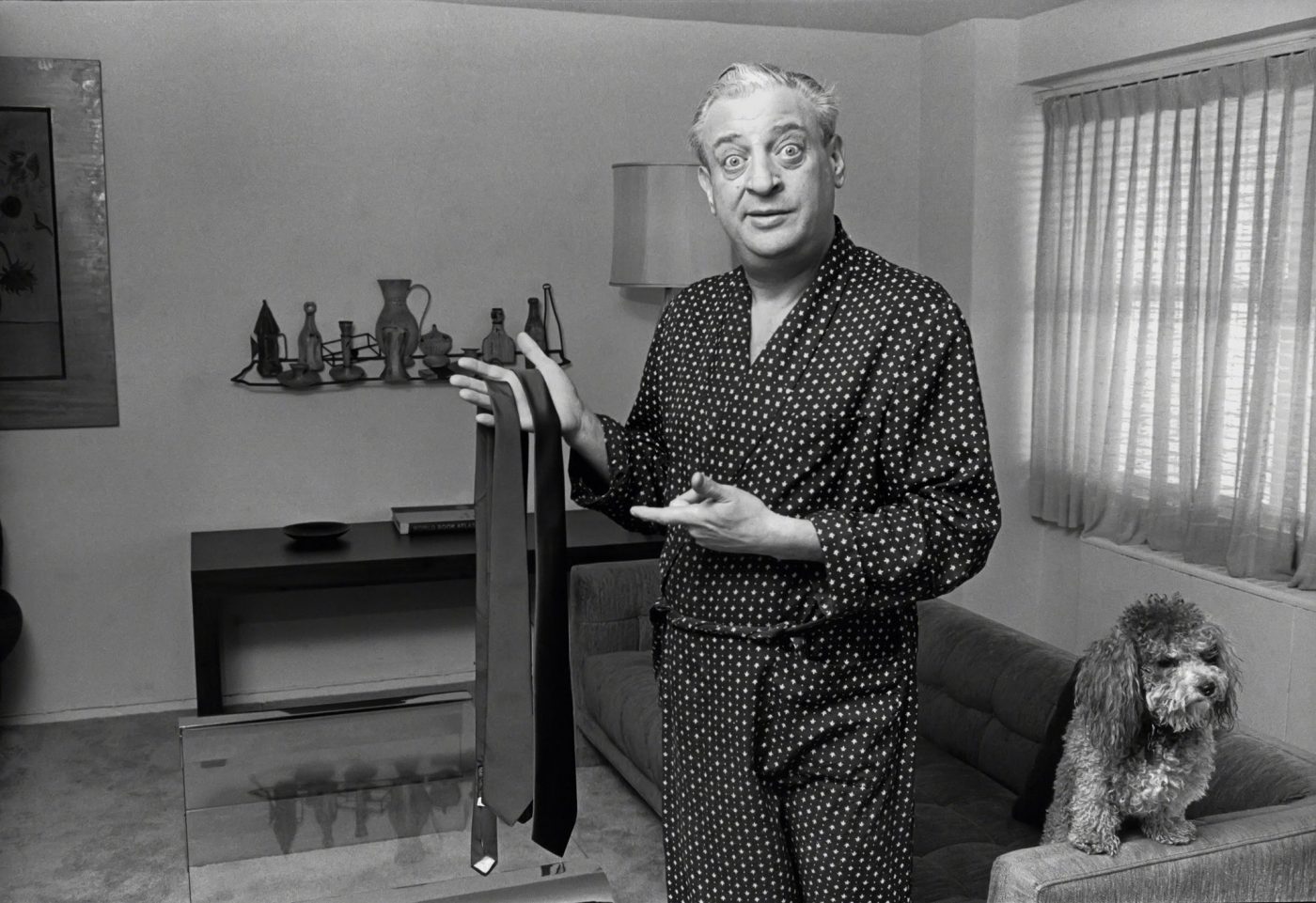

Imagine having no talent. Imagine being no good at all at something and doing it anyway. Then, after nine years, failing at it and giving it up in disgust and moving to Englewood, N.J., and selling aluminum siding. And then, years later, trying the thing again, though it wrecks your marriage, and failing again. And eventually making a meticulous study of the thing and figuring out that, by eliminating every extraneous element, you could isolate what makes it work and just do that. And then, after becoming better at it than anyone who had ever done it, realizing that maybe you didn’t need the talent. That maybe its absence was a gift.

These were the stations on the via dolorosa of Jacob Cohen, a.k.a. Rodney Dangerfield, whose comedy I hold above all others’. At his peak — look on YouTube for any set he did between 1976 and 1990 — he was the funniest entertainer ever. That peak was long in coming; by the time he perfected his act, he was nearly 60. But everything about Dangerfield was weird. While other comedians of that era made their names in television and film, Dangerfield made his with stand-up. It was a stand-up as dated as he was: He stood on stage stock-still in a rumpled black suit and shiny red tie and told a succession of diamond-hard one-liners.

The one-liners were impeccable, unimprovable. Dangerfield spent years on them; he once told an interviewer that it took him three months to work up six minutes of material for a talk-show appearance. If there’s art about life and art about art, Dangerfield’s comedy was the latter — he was the supreme formalist. Lacking inborn ability, he studied the moving parts of a joke with an engineer’s rigor. And so Dangerfield, who told audiences that as a child he was so ugly that his mother fed him with a slingshot, became the leading semiotician of postwar American comedy. How someone can watch him with anything short of wonder is beyond me.

“To be a comedian,” he said, “you have to get onstage and find out if you’re funny.” He wasn’t. During his first career, performing as Jack Roy, he was a singing waiter, used props, tried impressions. Even after his second coming — using a stage name devised by a club owner as a gag — and becoming a regular on “The Ed Sullivan Show,” he could be miserable. In a YouTube clip of him performing on “Sullivan” in 1969, Dangerfield’s face is the unsettling bluish-pink of raw chicken. The jokes — about getting directions, his wife’s driving, their apartment — keep bombing. The setups are too long; the delivery is too slow; the punch lines are so lame that you can hear the scattered laughter of distinct individuals. Even worse, he panders. “I’ll tell you, it’s nice to hear you laugh,” he says at one point. It’s almost unseemly.

In the decade that followed, Dangerfield eliminated everything from his act but the setups and punch lines. In his determination to unlock how they worked, he devised multiple jokes around the same setup, like a composer writing variations on a theme. “When I was born, I was so ugly the doctor slapped my mother” might be followed with “I was an ugly kid. When I was born, after the doctor cut the cord, he hung himself.” His body of work is a codex, a “Well-Tempered Clavier” of comedy.

Most comics use the setup and punch line like a nail and hammer, but Dangerfield used them as a theremin player uses her hands, to bring forth strange, unexpected effects. Some were so masterful and odd that they transcended linear logic. My favorite joke of his — “I told my dentist my teeth were going yellow. He told me to wear a brown necktie” — barely makes sense at first. It’s a bewildering piece of misdirection. But it works as a marvel of dream logic, a joke Kafka might have liked.

With other jokes the angle between setup and punch line was so acute that it momentarily stunned the audience, requiring an extra beat to sink in and creating opportunities of timing. You can watch one at the close of a Dangerfield set on the “Tonight” show. It’s Aug. 1, 1979, and he’s at the summit of his craft. As with the very best comedians, the laughter begins before he speaks. His delivery is angry, rapid-fire, leaving the audience no time to recover. The standup portion kills, but everyone knows the better part will happen at the host’s desk, where Johnny Carson, pulling on a cigarette, will gamely set him up.

In the chair, Dangerfield continues performing. He goes on a riff about being old (“My last birthday cake looked like a prairie fire”) and, with only seconds left in the segment, says: “At my age, I want two girls at once. If I fall asleep, they got each other to talk to.” The effect is of a tennis pro wrong-footing his opponent. The laughter is strangled, then builds. As the tendrils of comprehension are still making their way through the audience, Dangerfield turns to the guest next to him — none other than James Mason, owner of Hollywood’s most genteel speaking voice, squirming in powder-blue seersucker — and says, “What’s new with you?” Pandemonium erupts. Carson staggers out of his chair and laughs that hyena laugh that told you he was really laughing, then looks at Dangerfield and, gasping for breath, asks, “I assume you’re through?” Dangerfield flashes a rare look of satisfaction. Can there be sweeter revenge for all those years of getting no respect than achieving quantifiable perfection?

_____

Alex Halberstadt is the author of the forthcoming family memoir “Young Heroes of the Soviet Union.”

Source: Letter of Recommendation: Rodney Dangerfield

]]>