– News from elsewhere covered by Quincy Quarry News with commentary added.

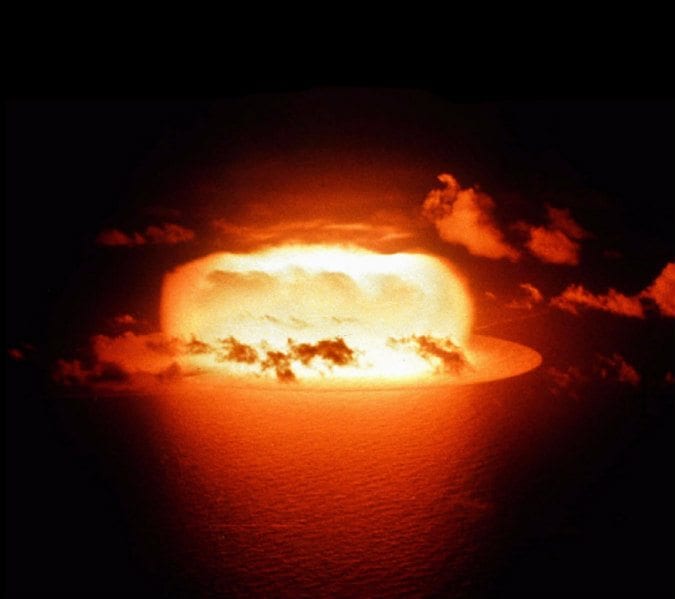

The $247 trillion global debt bomb.

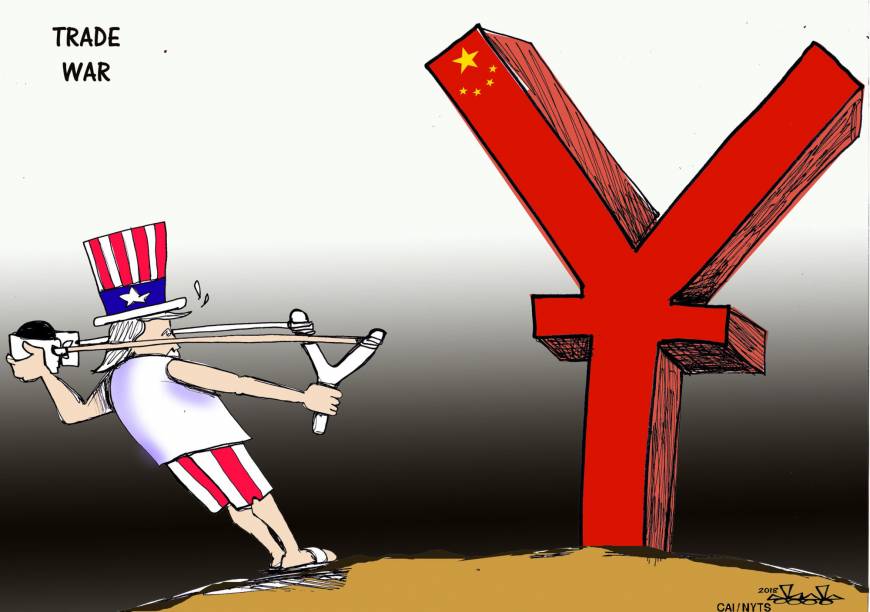

To service these debts requires rising incomes, while an expanding trade war threatens to squeeze incomes.

The untold story of the world economy — so far at least — is the potentially explosive interaction between the spreading trade war and the overhang of global debt, estimated at a staggering $247 trillion.

That’s “trillion” with a “t.”

Households, businesses and governments borrow on the assumption that they will service their debts either by paying the principle and interest or by rolling over the debts into new loans.

But this works only if incomes grow fast enough to make the debts bearable or to justify new loans.

When those ingredients go missing, delinquencies, defaults and (at worse) panics follow.

Here’s where the trade war and debt may intersect disastrously.

Since 2003, global debt has soared. As a share of the world economy (gross domestic product), the increase went from 248 percent of GDP to 318 percent. In the first quarter of 2018 alone, global debt rose by a huge $8 trillion.

The figures include all major countries and most types of debt: consumer, business and government.

But to service these debts requires rising incomes, while an expanding trade war threatens to squeeze incomes.

Note that the danger is worldwide – it’s not specific to the United States.

In a new report, the Institute of International Finance (IIF), an industry research and advocacy group, says that the debts of some “emerging market” countries (Turkey, South Africa, Brazil, Argentina) seem vulnerable to roll-over risk: the inability to replace expiring loans.

Debt can either stimulate or retard economic growth, depending on the circumstances. Now we’re approaching a turning point, according to Hung Tran, the IIF’s executive managing director: if debt growth is not sustainable, new lending will slow or stop. In turn, borrowers will have to devote more of their cash flow to servicing existing debts.

Tran describes the change this way: “(we had) a goldilocks economy, with decent economic growth. Inflation was nowhere to be seen, allowing central banks to … (keep interest rates low). You could always roll over your debt. However, the probability of this continuing is much less now. … Trade tensions are on the rise, and this has already impacted (business confidence) and the willingness to invest.”

Inflation is also creeping up. To stall its rise, the Fed is raising interest rates. Trade protectionism compounds the problem, because many non-U.S. companies borrow in dollars. But these loans must be repaid in dollars. If tit-for-tat protectionism dampens trade, getting those dollars will become harder. Loan delinquencies and defaults may rise.

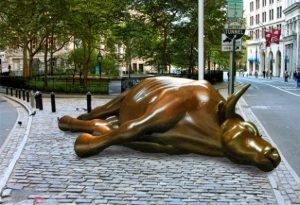

Tran isn’t predicting a full-scale panic resembling the 2008-09 financial crisis, and there are some reasons for optimism. For example, banks are better capitalized now than before the crisis.

What Tran is suggesting is a global shift away from debt-financed economic growth. The meaning of the $247 trillion debt overhang is that many countries (including China, India and other emerging-market countries) will be dealing with the consequences of high or unsustainable debts — whether borne by consumers, businesses or governments. There will be a collective impact on the global economy.

“If you are in a high-debt situation, you need to bring the debt down, either absolutely or as a share of GDP,” he said at the briefing. “[Either] will result in slower economic growth. You don’t have the borrowing needed to maintain strong investment and consumption spending.”

This may represent a final chapter to the 2008-2009 financial crisis. The low interest rates adopted by central banks were justified as necessary to avoid an even worse worldwide depression.

Critics conversely worried that cheap credit would rationalize risky lending that couldn’t survive higher rates.

We may soon discover who’s right.

Source: The $247 trillion global debt bomb | The Japan Times

QuincyQuarry.com

Quincy News, news about Quincy, MA - Breaking News - Opinion

No more posts